Natural convection is a fundamental heat transfer mechanism that plays an important role in numerous engineering applications and natural phenomena. Unlike forced convection, which relies on external forces to move fluid, natural convection happens spontaneously due to density differences in the fluid caused by temperature variations. This self-driven flow mechanism has made it a necessity in many engineering devices where passive cooling is preferred over active methods. As discussed in our previous article on Overall Heat Transfer Coefficient, understanding different heat transfer modes is crucial for effective thermal system design. Looking for practical applications? Explore our extensive collection of Natural Convection CFD Simulations using ANSYS Fluent to see how these principles are applied in real-world engineering problems.

Contents

ToggleIn this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what natural convection is, how it works, and why understanding it is crucial for engineers and scientists working with thermal systems. Natural convection meaning encompasses the physics behind how fluids move when heated without external forces, creating a fascinating and practical heat transfer process that occurs all around us.

What Is Natural Convection?

Natural convection, also known as free convection, is a type of heat transfer where fluid motion is generated by density differences in the fluid due to temperature gradients. When a fluid is heated, its molecules gain energy and move faster, causing the fluid to expand and become less dense. Natural convection is a type of heat transport where fluid motion is generated by buoyancy forces resulting from density changes within the fluid. These density variations typically arise from temperature differences, as described in our comprehensive article on Convective Heat Transfer. When a fluid is heated, it becomes less dense and rises, while cooler, denser fluid sinks, creating a natural circulation pattern. This process is governed by the principles outlined in the Energy Conservation Equation, which describes the relationship between fluid flow and heat transfer.

The natural convection meaning becomes clear when we observe everyday examples like hot air rising above a radiator or convection currents in a pot of boiling water. These are all instances of natural convection examples that demonstrate how heat naturally transfers through fluids without mechanical assistance. Understanding what is natural convection helps engineers design more efficient passive cooling systems and thermal management solutions.

The Physics Behind Natural Convection

The natural convection mechanism relies on three key physical principles:

- Thermal expansion: Most fluids expand when heated, becoming less dense.

- Buoyancy: Less dense fluids experience an upward force in a gravitational field.

- Continuity: As heated fluid rises, cooler fluid must flow in to replace it, creating a continuous circulation.

Buoyancy-driven flow is the fundamental principle behind natural convection heat transfer. When we ask, “what role does gravity play in natural convection?” the answer is critical – gravity is essential because it creates the pressure gradient that causes less dense warm fluid to rise and denser cold fluid to sink. Without gravity, natural convection would not occur as we know it.

The primary driving force for natural convection is the interaction between a fluid’s density difference and the gravitational field. When asking “how does density affect convection,” we must understand that even small temperature differences can create significant fluid movement because hot air is less dense than cold air. This principle explains why convection in fluids occurs spontaneously whenever temperature differences exist in a gravitational field.

The strength of natural convection is characterized by the Rayleigh number, which determines whether heat transfer occurs primarily through conduction or convection (we will discuss this parameter more in the next sections). Convective flow begins when the Rayleigh number exceeds a critical value (typically around 1708 for horizontal layers).

Several dimensionless numbers are used to characterize natural convection:

- Grashof number (Gr): Represents the ratio of buoyancy forces to viscous forces

- Rayleigh number (Ra): The product of the Grashof number and the Prandtl number, indicating the strength of natural convection

- Nusselt number (Nu): Represents the enhancement of heat transfer through a fluid layer as a result of convection

Figure 1: Natural Convection Phenomenon

As illustrated in Figure 1, natural convection creates a characteristic circulation pattern that shows the fundamental principles of heat transfer in fluid systems. The figure shows how warm fluid near the heat source (at bottom) becomes less dense and rises, while simultaneously cooling as it moves away from the source. As this fluid cools, it becomes denser and sinks, creating a continuous circulation pattern. This self-sustaining cycle is driven by buoyancy forces and density variations, making it an efficient mechanism for heat transfer in various applications.

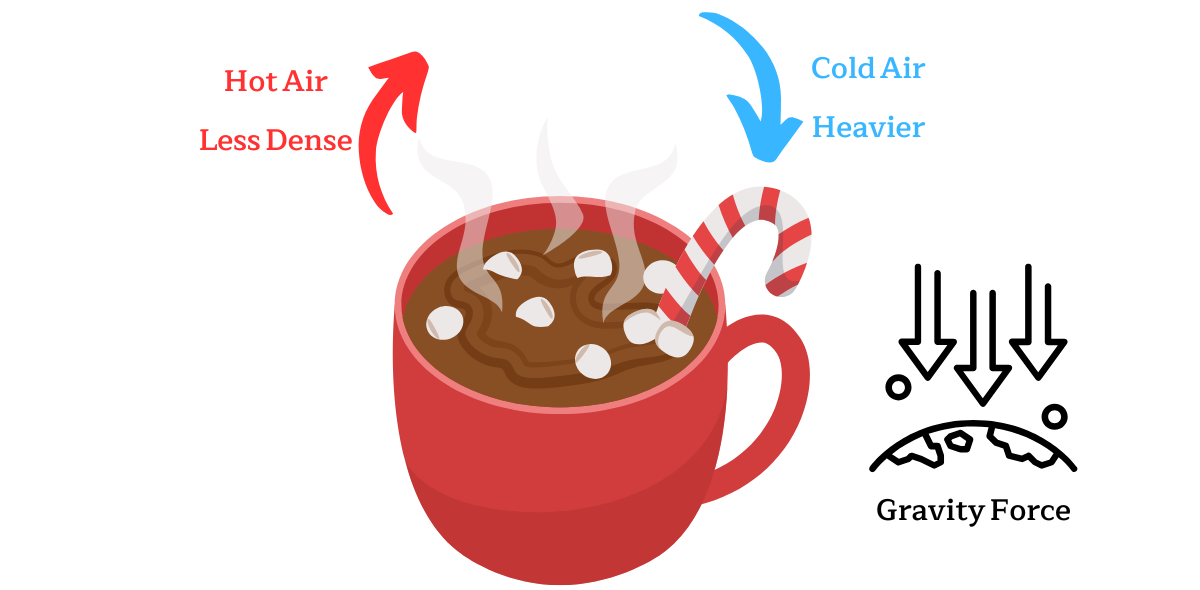

The physical process shown in Figure 2 occurs due to several key mechanisms. When the vertical surface is heated, it creates a temperature difference with the surrounding fluid, causing the fluid near the surface to become less dense. This density variation, combined with gravitational effects, generates buoyancy forces that drive the warmer fluid upward along the surface, forming a characteristic boundary layer. Within this layer, both temperature and velocity vary significantly, transitioning from the conditions at the heated surface to those of the surrounding fluid. This process is quantified by the Rayleigh number, which determines the strength of the natural convection effect and the nature of the flow within the boundary layer.

Figure 2: Vertical boundary layer in natural convection

Natural Convection Heat Transfer Coefficient

The heat transfer coefficient in natural convection varies significantly depending on the geometry and flow conditions. As explained in our article on Convective Heat Transfer, this coefficient is crucial for calculating the rate of heat transfer between a surface and the surrounding fluid. For natural convection, typical values range from 2-25 W/m²K for gases and 50-1000 W/m²K for liquids.

Table 1: Typical Natural Convection Heat Transfer Coefficients

|

Fluid Condition |

Heat Transfer Coefficient (W/m²K) |

|

Gases |

2-25 |

|

Liquids |

50-1000 |

| Air (free convection) |

5-25 |

|

Water (free convection) |

20-100 |

Practical Applications and Examples of Natural Convection

Natural convection plays a vital role in numerous engineering and everyday applications. In building systems, it drives HVAC operation and passive cooling strategies. Industrial processes rely on natural convection for cooling transformers, electrical equipment, and nuclear reactor components. In renewable energy, solar collectors and thermal storage systems utilize natural convection for efficient heat transfer. Two of the interesting cases that we’ve analyzed through CFD simulation are:

Natural Convection in a Narrow Annulus CFD Simulation: This simulation explores heat transfer in annular geometries, which is crucial for applications in electrical equipment, transformers, and nuclear reactor core cooling. Our detailed simulation, based on experimental validation, uses the Boussinesq model to accurately capture the natural convection phenomena in the narrow space between concentric cylinders.

Fig 3. Narrow Annulus CFD Simulation

Natural Convection from Heated Cylinder CFD Simulation: This study investigates the complex flow patterns around heated horizontal cylinders, with particular attention to confined spaces. The simulation validates experimental results and provides insights into how vertical and horizontal confinement affects the natural convection patterns, making it valuable for heat exchanger design and thermal management systems.

Fig 4. Heated Cylinder CFD Simulation

The following table shows a summary of natural convection benefits.

Table 2: Applications of Natural Convection

|

Application |

Industry |

Key Benefits |

|

Electronic Cooling |

Technology |

Silent operation, energy efficiency |

|

Solar Collectors |

Renewable Energy |

Passive operation, reliability |

|

HVAC Systems |

Building Services |

Energy savings, comfort |

|

Nuclear Reactors |

Power Generation |

Safety, reliability |

Natural convection in heat transfer applications continues to evolve as engineers develop more sophisticated passive cooling technologies. From the simple convection current in your coffee cup to complex natural draft cooling towers at power plants, the principles remain the same – heat-induced density differences create fluid movement that transfers thermal energy. These convection flow patterns can be leveraged for efficient and reliable thermal management across countless applications.

Natural Convection vs. Forced Convection

In heat transfer studies, it’s important to understand the difference between natural and forced convection. While both mechanisms transfer heat through fluid movement, they differ fundamentally in what drives that movement. Natural convection occurs when fluid flow is created by density differences due to temperature variations. No external mechanical devices are needed to move the fluid. In contrast, forced convection relies on external devices like fans, pumps, or blowers to create fluid movement. Thus, the key distinction between natural and forced convection lies in the driving mechanism of fluid motion.

Table 3: Comparison of Natural and Forced Convection

|

Parameter |

Natural Convection |

Forced Convection |

|

Driving Force |

Buoyancy |

External mechanical force |

|

Heat Transfer Coefficient |

2-25 W/m²K (gases) |

25-250 W/m²K (gases) |

|

Flow Control |

Less controllable |

Highly controllable |

|

Energy Consumption |

Lower |

Higher |

|

Application Cost |

Generally lower |

Generally higher |

Understanding natural convection vs forced convection is essential for selecting the appropriate heat transfer mechanism for specific applications. The difference between natural and forced convection affects how we design thermal systems for different needs. For example, when comparing natural vs forced convection, we see that natural convection offers energy efficiency advantages while forced convection provides higher cooling capacity.

When designing systems that utilize natural convection cooling, engineers must carefully consider geometry and material properties to optimize heat dissipation. In contrast, forced convection systems focus on fan or pump selection and airflow path design. Many modern systems employ a hybrid approach that uses forced convection when higher cooling capacity is needed and switches to natural convection for energy-efficient operation during lower heat loads.

Natural Convection Formula

The strength of natural convection is characterized by the Rayleigh number (Ra), which is the product of the Grashof and Prandtl numbers:

Where:

- g = gravitational acceleration

- β = thermal expansion coefficient

- Ts = surface temperature

- T∞ = fluid temperature

- L = characteristic length

- ν = kinematic viscosity

- α = thermal diffusivity

When studying natural convection, the Grashof number calculation is also important as it represents the ratio of buoyancy forces to viscous forces:

Gr = (gβ(Ts – T∞)L³)/ν²

Understanding these mathematical relationships is essential for predicting natural convection heat transfer in engineering applications. The natural convection equation allows engineers to calculate heat transfer rates without performing complex experiments for every scenario. Different geometries like vertical plates, horizontal plates, cylinders, and enclosures each have their own specific natural convection correlations that have been developed through extensive research.

For accurate predictions of natural convection heat transfer coefficient air values, these equations must account for the specific air properties at the operating temperature. Similarly, when working with water systems, the convection coefficient of water must be calculated using appropriate correlations for that fluid. These mathematical tools are vital for designing efficient natural convection cooling systems and predicting performance across various applications.

The Boussinesq approximation is a fundamental model used in natural convection simulations that simplifies the treatment of density variations in buoyancy-driven flows. The model assumes that density variations are sufficiently small to be neglected in all equations except the buoyancy term in the momentum equation. This is mathematically expressed as the following formula, where ρ₀ is the reference density, β is the thermal expansion coefficient, T is the local temperature, and T₀ is the reference temperature

Comparison with Ideal Gas Model and Limitations:

The Boussinesq approximation differs significantly from the ideal gas model in both application scope and limitations. While the ideal gas model accounts for density variations due to both temperature and pressure changes (ρ = P/RT), the Boussinesq approximation is valid only for small temperature differences (typically when ΔT/T₀ < 0.1). This limitation makes the Boussinesq model unsuitable for applications involving large temperature variations or compressible flows.

The document mentions that ANSYS Fluent offers both models, with the choice significantly impacting simulation accuracy. The Boussinesq model is preferred for natural convection in confined spaces and low-temperature applications like electronic cooling and HVAC systems, while the ideal gas model is better suited for high-temperature applications or cases where compressibility effects cannot be ignored.

Natural Convection in ANSYS Fluent

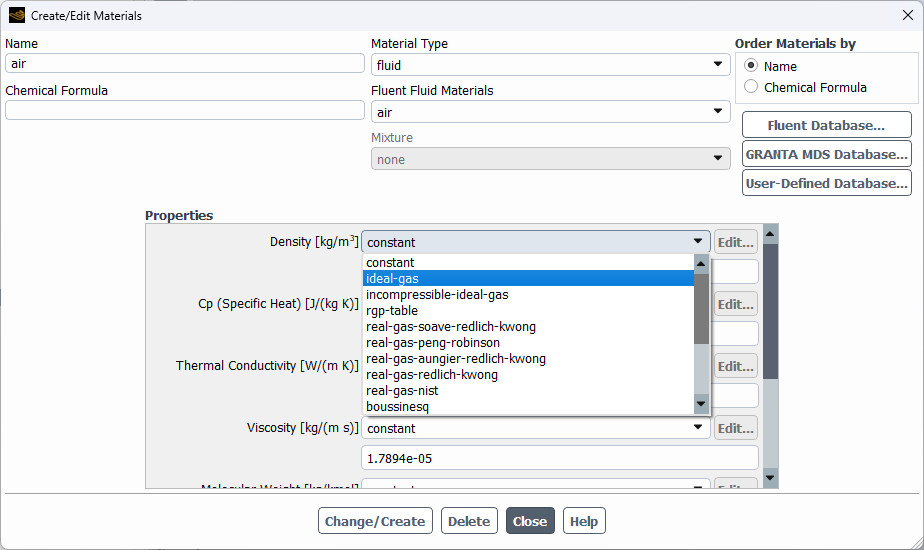

As explained in our article on Energy Conservation Equation, ANSYS Fluent provides robust availabilities for simulating natural convection phenomena. The software utilizes different density models including Ideal Gas, Incompressible Ideal Gas, and Boussinesq approximation for modeling buoyancy-driven flows, which is very important for cases involving Conjugated Heat Transfer.

Fig 5. Different density models in ANSYS Fluent software

As shown in Figure 5, ANSYS Fluent offers various density models for natural convection simulation. The choice of model significantly impacts the accuracy of results, particularly in cases involving temperature-dependent density variations.

Key considerations for natural convection simulation include:

- Proper mesh refinement near walls to capture boundary layer effects

- Selection of appropriate turbulence models

- Setting up correct boundary conditions

- Enabling gravity effects

- Defining material properties accurately

As demonstrated in our Conjugated Heat Transfer simulations, the interaction between solid and fluid domains is particularly important in natural convection problems.

Conclusion

Natural convection represents one of nature’s elegant solutions for heat transfer in fluid systems. By harnessing the simple principle that warm fluids rise and cool fluids sink, natural convection heat transfer enables efficient thermal management without moving parts or external power sources.

From the smallest electronic components to vast atmospheric systems, natural convection plays a crucial role in countless applications. Understanding its principles allows engineers to design more efficient passive cooling systems, architects to create more comfortable buildings, and scientists to better predict environmental phenomena.

The study of natural convection continues to evolve, with ongoing research into enhancing its effectiveness through surface modifications, new materials, and optimized geometries. As energy efficiency becomes increasingly important, the value of passive heat transfer mechanisms like natural convection grows even more significant.

Whether you’re designing a heat sink for electronics, planning a passive solar building, or simply curious about why your coffee steam rises, the principles of natural convection provide insights into the invisible yet powerful thermal currents that surround us every day.

By embracing and optimizing natural convection in our designs, we can create more sustainable, reliable, and efficient systems that work in harmony with nature’s fundamental principles.

FAQ

Question 1: What are the three essential requirements for natural convection to occur in a system?

Natural convection requires a temperature difference to create density variations, a gravitational field for buoyant forces, and a fluid medium that can move freely.

Question 2: How does the heat transfer coefficient differ between liquids and gases in natural convection?

Liquids have higher heat transfer coefficients (50-1000 W/m²K) compared to gases (2-25 W/m²K) due to their greater density and thermal properties.

Question 3: What is the significance of the Rayleigh number in natural convection?

The Rayleigh number determines convection strength and indicates whether heat transfer occurs primarily through conduction or convection. The critical value is approximately 1708.

Question 4: How does natural convection benefit electronic cooling applications?

Natural convection provides silent operation and energy efficiency in electronic cooling, requiring no external power for fluid movement while effectively removing heat.

Question 5: What key factors must be considered when simulating natural convection in ANSYS Fluent?

Important considerations include proper mesh refinement, turbulence model selection, boundary conditions, gravity effects, and accurate material property definitions.

Related Blogs

What Is Buoyancy?

Understanding buoyancy is essential for grasping natural convection since buoyancy forces are the primary driving mechanism that causes warmer, less dense fluids to rise and create convection currents.

Conjugate Heat Transfer (CHT)

In real-world applications, natural convection rarely occurs in isolation but combines with conduction through solid surfaces, making conjugate heat transfer analysis crucial for accurate thermal predictions.

What is PMV? What is PPD? Basics of Thermal Comfort

Natural convection plays a vital role in indoor thermal comfort by creating air movement patterns that affect how occupants perceive temperature and comfort levels in buildings.

What is a Dimensionless Number?

The analysis of natural convection relies heavily on dimensionless numbers like the Rayleigh, Grashof, and Nusselt numbers to characterize flow regimes and predict heat transfer rates.

Data Center Cooling Systems

Modern data centers increasingly incorporate natural convection principles in their cooling strategies, using hot aisle/cold aisle configurations and passive cooling elements to improve energy efficiency.