Noise is everywhere in the engineering world. From the roar of a jet engine to the hum of a computer fan, understanding and controlling sound is critical. In modern engineering, we use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) not just to see how fluids flow, but also to hear them. This guide is the first part of a series that will explain the fundamentals of Acoustics CFD. We will start with the basics and build a strong foundation for understanding how we can predict and analyze noise using simulation.

Contents

Toggle

What are Acoustics and Aeroacoustics?

To begin our journey into Acoustics Fluent simulations, we must first understand two key terms: Acoustics and Aeroacoustics.

What is Acoustics? The word Acoustics comes from a Greek word that means “audible,” or something that can be heard. At its core, acoustics is the branch of physics that studies mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids. This includes things like vibration, ultrasound, and of course, sound. In simple terms, acoustics is the science of sound. It deals with how sound is created, how it moves, and how it is received.

What is Aeroacoustics? Aeroacoustics (or Aero-Acoustics) is a specific branch of acoustics. It focuses on noise that is generated by the movement of a fluid. When a fluid, like air, moves in a turbulent way, it creates changes in pressure and density.

- Turbulent fluid flow is chaotic and unsteady.

- This chaotic motion creates pressure fluctuations.

- These pressure fluctuations travel away from the source as sound waves.

Therefore, Aeroacoustics CFD is the science of predicting sound that comes from fluid flow. The same fundamental equations of fluid dynamics that we use to calculate flow fields also contain the information needed to analyze the sound that the flow produces.

Figure 1: A visual diagram showing a turbulent flow from a jet engine exhaust with sound waves radiating outwards

Why Does Aeroacoustics Matter in Engineering?

Understanding and controlling noise is extremely important in modern engineering. Unwanted noise from products can be a major problem. Think about the noise from:

- Aircraft engines and landing gear

- High-speed trains

- The fans in your computer or air conditioner

- Wind turbines

- Cars and trucks moving at high speed

A perfect example of this is the design of modern propellers. Traditional propellers can be very noisy. Using Aeroacoustics CFD, engineers can simulate new designs, like the toroidal propeller, to significantly reduce the generated noise while maintaining performance. You can explore a detailed simulation of this advanced application in our Toroidal Propeller Aeroacoustics Simulation using Broadband Noise Sources Model tutorial.

Figure 2: By predicting noise with CFD, we can solve noise problems at the design stage, saving time and money

The Physics of Sound: Basic Theory

To perform a meaningful acoustic simulation in Fluent, we need to understand the basic physics of sound. Sound is not just something we hear; it is a physical phenomenon with properties we can measure and calculate. This section explains the fundamental concepts of sound waves, pressure, intensity, and the scales we use to measure them.

Understanding Sound as Pressure Waves

As we learned, sound is a wave that travels through a medium like air or water. More specifically, a sound wave is a series of rapid pressure fluctuations. Imagine dropping a stone in a calm pond. The ripples that travel outwards are like sound waves. In the air, these “ripples” are tiny, quick changes in the local pressure that move away from the noise source.

In an Acoustics CFD analysis, our main goal is to calculate these pressure fluctuations as they change over time and space.

Sound Intensity vs. Sound Pressure

When we talk about how “loud” a sound is, we are often talking about its energy. The two most important ways to measure this are with sound intensity and sound pressure.

- Sound Intensity (I): This is the amount of energy the sound wave carries per unit of area. Think of it as the power of the sound wave.

- Sound Pressure (p): This is the local pressure change caused by the sound wave. This is what we can actually measure with a microphone and what we typically solve for in CFD.

Luckily, these two are directly related. we can link them with a formula. The most important relationship in aeroacoustics connects sound intensity directly to sound pressure. The formula is:

![]()

Where:

- I is the Sound Intensity (in Watts/m²)

- p is the acoustic pressure fluctuation (in Pascals)

- ρ (rho) is the density of the fluid (e.g., air or water)

- c is the speed of sound in that fluid

This equation is powerful because it allows us to perform a sound pressure level calculation in CFD and use the result to understand the sound’s energy.

Figure 3: A schematic showing the definition of Sound Intensity. It represents the acoustic energy (power) flowing through a specific unit of area, a key metric for understanding the strength of a sound wave.

The Decibel (dB) Scale

The range of sound intensity that humans can hear is enormous. The quietest sound we can detect is trillions of times less intense than a sound that causes pain. Working with such large numbers is difficult. To solve this, we use the decibel (dB) scale. It is a logarithmic scale. This means that for a huge increase in sound intensity, the decibel value only increases by a small amount, making the numbers much easier to manage.

The sound level in decibels (β) is calculated from intensity using this relation:

![]()

Where I₀ is the reference sound intensity, which is set at the threshold of human hearing (the quietest possible sound we can hear).

Figure 4: A chart comparing common sounds on the decibel (dB) scale. The logarithmic scale makes it easier to represent the huge range of sound levels we experience, from a quiet whisper to a loud jet engine.

Sound Pressure Level (SPL): The Standard Measurement for Noise

Because it is much easier to measure pressure than intensity, the most common way to describe a noise level is using Sound Pressure Level (SPL). It is also measured in decibels (dB). The formula for SPL is very similar, but it uses pressure instead of intensity:

![]()

Here, p is the acoustic pressure we calculated, and p_ref is the reference pressure. You might wonder why the formula uses ‘20’ instead of ‘10’. This is because intensity (I) is proportional to pressure squared (p²). The rules of logarithms bring the ‘2’ from the power down, which multiplies the ‘10’ to become ‘20’.

Figure 5: A visualization of Sound Pressure Level (SPL). This is the standard measurement for noise in CFD and is calculated from the pressure fluctuations solved in the simulation.

Crucial Point for ANSYS Fluent Users: The Reference Pressure

The value of the reference pressure (p_ref) is extremely important and it changes depending on the fluid you are simulating. Setting this value correctly in the Acoustics Fluent module is essential for getting accurate dB results.

- For simulations in Air, the standard reference pressure is: p_ref = 20 micropascals (20 x 10⁻⁶ Pa)

- For simulations in Water or other liquids, the standard reference pressure is: p_ref = 1 micropascal (1 x 10⁻⁶ Pa)

Using the wrong reference pressure will lead to incorrect results in your acoustic simulation Fluent setup. All acoustic results, like noise contour plots, are typically shown in terms of SPL in decibels.

Aeroacoustics Fundamentals: How Flow Becomes Sound

Now that we understand the physics of a sound wave, we need to connect it to fluid flow. How exactly does a moving fluid, like air or water, create noise? This is the central question of aeroacoustics.

How Turbulent Flow Generates Noise

As we mentioned earlier, the source of aeroacoustic noise is turbulent flow. A smooth, laminar flow is quiet. However, when a flow becomes turbulent, it is full of chaotic, swirling structures called eddies. These eddies cause the local fluid pressure and density to fluctuate rapidly.

These rapid pressure fluctuations created by turbulence are the direct source of sound waves. The sound waves then travel, or propagate, away from the turbulent region, and we hear them as noise.

Lighthill’s Acoustic Analogy: The “Source” of the Sound

The direct simulation of noise generation is extremely complex because the equations of fluid motion (the Navier-Stokes equations) are very difficult to solve. In the 1950s, a physicist named Sir James Lighthill developed a revolutionary approach called the Lighthill acoustic analogy.

Figure 6: A portrait of Sir James Lighthill, whose pioneering work on the “acoustic analogy” provided the mathematical foundation for modern Aeroacoustics CFD.

Instead of solving the full, complex equations directly for sound, he rearranged them. He manipulated the equations of motion into the form of a classic wave equation, which describes how sound travels through a still fluid. All the complicated terms related to the fluid flow were moved to the other side of the equation, where they act as a source term. The governing equation for the Lighthill acoustic analogy is:

![]()

- Left Side

This is the Wave Equation. It describes how sound waves (pressure fluctuations ρ’) propagate through a fluid at the speed of sound (c₀).

This is the Wave Equation. It describes how sound waves (pressure fluctuations ρ’) propagate through a fluid at the speed of sound (c₀). - Right Side

: This is the Source Term. It contains the Lighthill stress tensor, Tᵢⱼ, which represents all the effects of the fluid flow that generate the noise.

: This is the Source Term. It contains the Lighthill stress tensor, Tᵢⱼ, which represents all the effects of the fluid flow that generate the noise.

Lighthill’s analogy allows us to treat the complex turbulent flow as a source of sound in an otherwise quiet fluid. This is the fundamental concept behind most modern Computational Aeroacoustics methods, including the models used in ANSYS Fluent.

Three Types of Aeroacoustic Noise Sources

Lighthill’s work, which was later extended by Ffowcs Williams and Hawkings (leading to the FWH model), helps us group the sound sources into three main types. Understanding these source types is critical for setting up an effective Acoustics CFD simulation in a program like ANSYS Fluent.

| Source Type | Simple Description | Common Engineering Example |

| Monopole (Thickness Noise) | Caused by a change in mass or volume. Imagine a balloon being quickly inflated and deflated. | The exhaust of a jet engine, where a volume of hot gas is rapidly pushed into the air. |

| Dipole (Loading Noise) | Caused by unsteady forces acting on a surface. Imagine a flag flapping in the wind. | A rotating propeller blade or fan blade pushing on the air. This is often the dominant noise source for rotating machinery. |

| Quadrupole (Shear Noise) | Caused by the turbulent motion and shear within the fluid itself, away from any surfaces. | The mixing noise created in the turbulent shear layers of a high-speed jet stream. |

Figure 7: An illustration of the three primary aeroacoustic sound sources. The pulsating sphere (monopole), the surface with unsteady forces (dipole), and the turbulent eddy (quadrupole) are the building blocks of noise generation in fluid flow.

In most real-world engineering problems, especially in Aeroacoustics Fluent simulations, the noise you hear is a combination of these three source types. A successful acoustic analysis depends on correctly identifying and modeling the most important sources for a specific application.

Overview of Acoustic Modeling Approaches in ANSYS Fluent

When we want to perform an Acoustics CFD simulation, there is not just one way to do it. As explained, ANSYS Fluent offers several different models. The choice of which model to use depends on the specific problem, the required accuracy, the available computational power, and what you want to learn about the noise.

These methods are generally divided into three main families:

- The Direct Method: This solves the fluid flow and the sound generation at the same time.

- The Hybrid Methods: These solve the fluid flow first and then use that data to calculate the sound in a second step.

- The Broadband Noise Source Models: These use a steady-state flow solution to quickly estimate the overall sound power.

Here is a table summarizing the different approaches available for acoustic simulation in Fluent.

| Model / Approach | Simple Description | Key Characteristics / Use Case |

| The Direct Method (DNS/LES) | Calculate fluid flow and the sound it makes at the very same time. Everything is solved together in one complex, transient simulation. | • Very accurate. • Solves flow and acoustics simultaneously (Coupled). • Limitation: Extremely expensive and requires very fine mesh and small time steps. • Best for academic research or analyzing the noise source itself, not for far-field noise. |

| Hybrid Methods (Decoupled Approach) | First, solve the fluid flow with a standard transient CFD simulation. Then, use that flow data as a source to calculate the sound separately. | • More computationally efficient than the Direct Method. • This is the most common approach in industrial CFD |

| The FWH Model (Integral Approach) |

A hybrid method that uses the flow data on a surface (like a propeller blade or car body) to predict the noise that travels far away to specific listener points (receivers). | • The most widely used aeroacoustics model in industry. • Excellent for far-field noise prediction. • Limitation: Only works for open-space problems (not for enclosed ducts or pipes). |

| The Wave Equation Model (Differential Approach) |

A hybrid method that calculates how sound travels throughout a defined CFD domain, including inside enclosed spaces. | • Can be used for enclosed spaces like pipes and HVAC ducts. • Limitation: Assumes incompressible flow (constant density). |

From Time to Frequency: The Importance of FFT

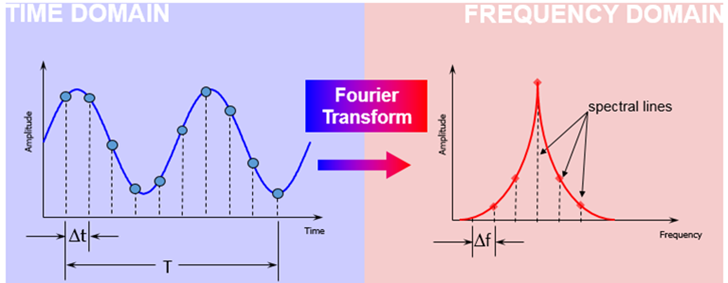

When we run a transient acoustic simulation, such as the FWH analysis of a building, our direct result is a pressure signal. This signal shows how the pressure at a specific point (a receiver or “microphone”) change over time. However, just looking at this complex, wavy line of pressure versus time does not tell us much about the character of the noise.

To truly understand the sound, we need to see which frequencies are present and which are the loudest. This requires us to convert the information from the time domain (how it changes over time) to the frequency domain (what frequencies it contains).

Why We Analyze Sound in the Frequency Domain

In fact, any complex sound wave can be created by combining several simple sinusoidal waves, each with its own frequency and amplitude. Analyzing sound in the frequency domain is like taking apart a complex machine to see all of its individual components.

It allows us to answer critical engineering questions:

- What are the dominant, or loudest, frequencies in the noise?

- Is the noise a low-frequency rumble or a high-frequency whistle?

- Are there sharp peaks at specific frequencies (tonal noise) or is the sound energy spread out over a wide range (broadband noise)?

Knowing the frequency content of the noise is essential for diagnosing the source of the noise and designing effective solutions to reduce it.

Figure 8: A complex pressure signal over time (left) is transformed into a simple frequency plot (right), revealing the dominant noise frequencies that are otherwise hidden

A Simple Explanation of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

The mathematical process for converting a signal from the time domain to the frequency domain is called a Fourier Transform. Doing this by hand is very difficult. Therefore, computers use a very fast and efficient algorithm called the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT).

In Acoustics Fluent, the FFT is a critical post-processing tool. Here is how it works in practice:

- Get the Time Signal: First, we run a transient simulation, like in our Aeroacoustics Analysis on a Building tutorial. The simulation calculates the pressure fluctuations over a period of time at one or more receiver locations.

- Apply the FFT: We then take this pressure-time data and use the FFT function in the post-processor.

- Analyze the Frequency Plot: The FFT creates a new plot. The horizontal axis (x-axis) shows the frequency (in Hertz, Hz), and the vertical axis (y-axis) shows the Sound Pressure Level (SPL) (in decibels, dB).

The peaks on this new plot immediately and clearly show us the frequencies where the most acoustic energy is present. If we see a large peak at a certain frequency, we know that this is a problem frequency that we need to investigate. The FFT is the tool that turns a complex time signal into a clear and understandable frequency spectrum, allowing engineers to pinpoint the character of the noise.

Figure 9: A sample Sound Pressure Level (SPL) plot from an ANSYS Fluent acoustic analysis. The peaks on the graph clearly show the dominant frequencies in the noise, helping engineers pinpoint the source of the problem.

Conclusion

In this blog, we have covered the essential foundations of Aeroacoustics CFD. We started with the basic physics of sound and learned how unsteady, turbulent flow generates noise through the principles of Lighthill’s analogy. We looked at the main computational approaches available in modern CFD solvers like ANSYS Fluent, from the efficient FWH model to the fast Broadband Noise models. Finally, we saw that to properly understand our simulation results, converting them from the time domain to the frequency domain using an FFT is a critical final step.

This provides the foundation you need for our next articles. In our next blog, we will explore the different acoustic models in ANSYS Fluent in much more detail, showing how to set them up for different engineering problems.